Day 2

Today

- Reading journal day 1 debrief

- Ways to run Python code

- How to get started with day 2 reading

- Crash Course in Bio / Overview of mini-project 1

- Going Beyond: do the work below on this page

For Next time you Should

- Read TP Ch. 6.1-6.4 and Ch. 7

- Finish setting up your environment

- Complete Day 2 (and Day 1) Reading Journal before noon on 1/24

- read the mini-project 1 assignment

- Start Working on part 1 of MP1

A Note About Pair Programming

We encourage you to work in pairs. If you do so, be sure to occasionally trade off who is “driving” (i.e. who is actually typing the commands into Python). If you have not gotten your environment setup, try working with a partner who has.

A Note About Class Exercises and Pacing

Given the diversity in experience in programming for the students in this course, the amount of time it takes each person to get through the class exercises will vary considerably. In my experience, these differences diminish as the course goes on, but at the beginning of the semester it can be quite dramatic. If you get done early, we have often given other exercises you can try. However, if you find yourself with nothing to do, then try to find other exercises from Think Python, make up your own exercise, or think of interesting questions to ask the instructors! (Just don’t be bored).

Introduction to Python!

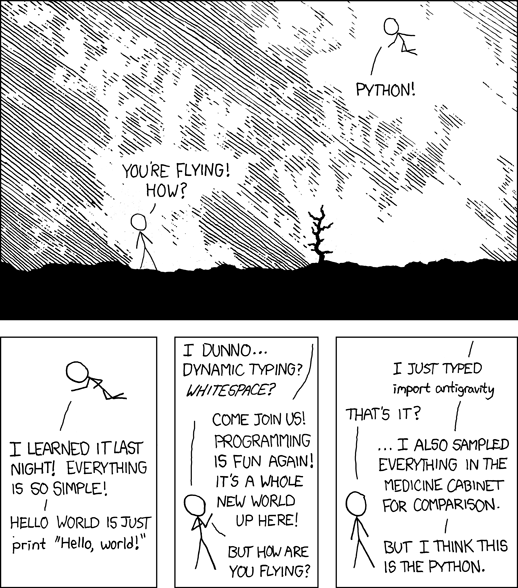

Let’s start with the obligatory Python xkcd comic.

Today you will begin your journey to mastering Python and obtaining this potent superpower.

Python as a Calculator

In addition to being an awesome programming language, Python is a pretty great calculator (as you saw in the reading). Let’s make sure we have the basic ideas down. Let’s fire up the Python interpreter and try out TP Exercise 1.2:

Start the Python interpreter and use it as a calculator. Python’s syntax for math operations is almost the same as standard mathematical notation. For example, the symbols +, - and / denote addition, subtraction and division, as you would expect. The symbol for multiplication is *.

If you run a 10 kilometer race in 43 minutes 30 seconds, what is your average time per mile? What is your average speed in miles per hour? (Hint: there are 1.61 kilometers in a mile).

Now with a partner try one of the three parts from TP Exercise 2

Executing Python Scripts

Learning how to write our first Python program is easy (in fact, all you have to do is read the xkcd comic and the code for Hello World is right there!). What we need to do next is to understand how to run (or execute our Python code). There are quite a few methods for executing Python code, and it helps to be familiar with all of them. Depending on the situation, you may choose a different route for running your program.

Method 0: In the browser as a Jupyter Notebook

This is what you’ve been using for the reading journals.

In the bash command line, enter:

$ jupyter notebook

This opens a browser window where you can open existing notebook files in the current directory, or create new ones.

Method 1: from the command line (usually in a “terminal” program)

First, we’ll create a simple Python script and save it in a file called hello.py.

"""

My first Python program!!

All royalties obtained from using this program belong to the SoftDes teaching team.

"""

print("Hello, world!")

In order to execute our new program we open a terminal, navigate (using Linux commands such as cd and ls) to the directory (folder) where we saved hello.py, and then execute the command:

$ python3 hello.py

Executing this command should produce the following output.

Hello, world!

Method 2: through your IDE

The instructions for doing this will depend on which IDE you are using, but if you are following along with Atom and the Hydrogen plug-in, all you need to do to run your program is press Control+Command+Return).

You can use the Atom Command Palette to find this command. Press Cmd+Shift+P to open the command palette, and type “hydrogen” to see a list of Hydrogen commands. “Hydrogen: Run All” is shown with its keyboard shortcut. This means that pressing that key runs that command.

Method 3: inside the Python interpreter

This method is deprecated. It works, but it’s not particularly useful. It’s listed here because it was adapted from a Python 2 technique that was more useful. it will be removed from future versions of the course.

You can execute Python scripts from within the Python interpreter (when running in interactive mode). To do so execute the following command from the Python prompt.

>>> exec(open('hello.py').read())

Method 4: inside the IPython interpreter

In general IPython is a superior option to the basic python interpreter if you want to execute Python in interactive mode. There are lots of advantages to IPython (here is a good list), but one of my favorites is tab completion. Open up IPython by executing the command ipython. At the IPython command prompt type “run he” and then hit the tab key. IPython should complete the command to run hello.py. Now if you press Enter, the code will execute (as in Method 3).

Exercise for the class: Now that you have seen these methods of invoking Python code, convert your solution to TP Exercise 2.4 into a Python script, and then execute the Python script using at least two of the methods above.

Variables, Expressions, and Statements

Variables are one of the most fundamental concepts in programming because they let you put a name to a value. Once you give something a name, you can refer to it in other parts of your code! A great way to understand variables is to draw a state diagram. Let’s do a quick example on the board that will help us understand how variables work, and will also give us practice with state diagrams.

x = 5

y = 4

print(x)

x = y

y = y + 1

print(x)

print(z)

z = 5

Here is another program that solves the problem above. It also demonstrates some good use of commenting. Let’s draw the state diagram after each line of the program.

# Compute start time of the run in hours since midnight

current_time = 6 + 52/60.0

easy_pace = 8 + 15/60.0 # minutes / mile

tempo_pace = 7 + 12/60.0 # minutes / mile

# update current time AFTER the run

current_time = current_time + easy_pace/60.0*2 + tempo_pace/60.0*3

print(current_time)

Calling Functions

Functions are another incredibly important concept in programming. They key advantage of functions is abstraction. That is, we can execute very complex operations by simply stating the name of the operation we’d like to perform and the value we’d like to perform it on. We don’t have to worry about how the operations are actually carried out (they are abstract to us when we call the function).

To see some examples, let’s use some of Python’s math functions.

Python has a multitude of built-in functions, a big standard library of modules, as well as additional user contributed modules. With a partner, either first think of a function you’d like to be able to execute in Python and see if you can figure out whether you can find that function somewhere in the Python universe, or check out some of the Python documentation and play around with some of the functions discussed therein.

Writing Our Own Functions

While there are quite a bit of great Python functions that we can easily incorporate into our program, we are very quickly going have the need for writing our own functions (for instance on the first mini-project). Let’s create our first function.

def multiply_by_two(x):

"""Multiply the input value by 2 and print the result.

x: the value to multiply by 2

"""

print(2*x)

The first thing to note is the docstring. The docstring should give a clear indication of what the function does. The one above is perhaps unnecessarily wordy (see this document for guidelines), but it does the job. Once we have the docstring down, we need to get our heads around how we call this function, and what happens when we call the functions. We will do both of these by learning about stack diagrams. (the NINJAs and I should have examples on the board).

You will notice that this function does not have a return value (what happens if you try and execute >>> print(multiply_by_two(3.0))?).

With a partner try TP Exercise 3.1. If you finish that, try TP Exercise 3.2 and 3.4.

Conditionals

Conditionals allow you to execute various blocks of code depending on whether a condition is true or false. Note, for more details on Boolean expressions and logic you should consult the reading. Here is an example:

def print_absolute_value(x):

"""Print the absolute value of the input value x."""

if x >= 0:

print(x)

if x < 0:

print(-x)

The key thing to keep in mind is that the expressions x >= 0 and x < 0 evaluate to either True or False (depending on what the value of x is). If the expression given to the if statement evaluates to true, then the block of code is executed. A common mistake that programming beginners make is to use the following more verbose form:

def print_absolute_value(x):

"""Print the absolute value of the input value x."""

if x >= 0 == True:

print(x)

if x < 0 == True:

print(-x)

The == True is unnecessary, but it will have the same effect. How come?

Optionally, an if statement can have a corresponding else statement. Using this we could rewrite our function as:

def print_absolute_value(x):

"""Prints the absolute value of the input value x."""

if x >= 0:

print(x)

else:

print(-x)

These are both correct. Is one better than the other? How come? Is it the case that the following two programs will always do the same thing no matter what statements are placed within the if or the else statement?

Program 1:

if x >= 0:

# do something

if x < 0:

# do something else

Program 2:

if x >= 0:

# do something

else:

# do something else

In addition to if and else, Python allows for 0 or more elif statements.

The Python interpreter will first check the if condition; if it is true it will execute that block of code and then jump to the end of the entire block.

If it is not true it will keep checking elif statements until one of them matches.

If one matches, that one will be executed and then we will jump to the end of the entire block.

If none of the elifs are true, then the else branch will be executed if it exists, and if no else branch is present nothing will happen.

Here is an example. With a partner, create a Python script with this function definition. Try calling the function with a few values. Does it do what you expect?

def print_num_nonnegative(x, y):

"""Print 0 if both x and y are negative, 1 if one of them is non-negative, and two if they are both non-negative."""

count = 0

if x >= 0:

count = 1

elif y >= 0:

count = 1

elif x >= 0 and y >= 0:

count = 2

else:

count = 0

print(count)

To close things out we will briefly discuss a few approaches to debugging as a class. These approaches will come up again and again throughout this course.